This part of the marginalia may be difficult to explain. I don’t know if it will make a lot of sense to people who speak English. It has to do with the voice of the story. The voice is a different thing than the narrator, or the person telling the story.

We just established who the storyteller is — Karen, Anna, and sometimes MWe. But the voice is how the teller sounds when they tell the story. The tone. The style. In other words, what Karen or Anna or MWe sound like as the narrator.

And we’ve decided that we both want to speak, as much as possible, in a way that actually isn’t that common in English.

Does this make sense so far?

~ Karen ~

You think so deeply, Anna. Just try.

~ Anna ~

People impact each other. We both cause impact and are impacted.

This is a fundamental truth that my mother has known in her bones her entire life.

My mother tells her story to me, and I receive it. I tell her story to you, the reader, and you receive it. I am both a receiver and a doer at the same time. I both learn and invent. Impacted by my mother and impacting our readers.

My mother shares her story, and she is her story. She is both a doer, engaging in storytelling, and a receiver, being witnessed by others for who she is and what her life has been. She is both telling her story and learning to see her story as important to tell. Impacting my ability to help her craft her story and impacted by our readers and their perceptions of her.

This is also exactly what happens when you teach kids through a process called co-active movement, a strategy that my mother believed in early on as an educator. Basically, when you move in tandem with a child, you learn together. Both of you do actions, each for yourself. Both of you are perceived as knowing things and learning things. You invent yourselves alongside each other. That is the point of view of this book. My mother calls it co-living.

By the time my mother got to the United States in the early 70s and nearing the age 30, she had already adopted psychologist Jean Piaget’s view on education:

“Children have real understanding only of that which they invent themselves, and each time that we try to teach them too quickly, we keep them from reinventing it themselves.”

Piaget called for teachers to stop being lecturers, to stop handing out ready-made answers. Instead, Piaget wanted teachers to act as instigators of research, initiative, and invention. Piaget wanted adults and children to practice what would come to be known as co-learning. Co-learning is a style of education where everyone learns together, everyone brings ingenuity and wisdom to the learning process, and at the end of the day, everyone learns.

My mother understood that this co-learning model was bigger than education and was part of how we live. Some core part of her sensed from a very young age that medical attention for her disability was too often about her being a passive receiver of care. Doctors and her parents were the active agents of change in her childhood — change that she mostly didn’t need or want or deserve.

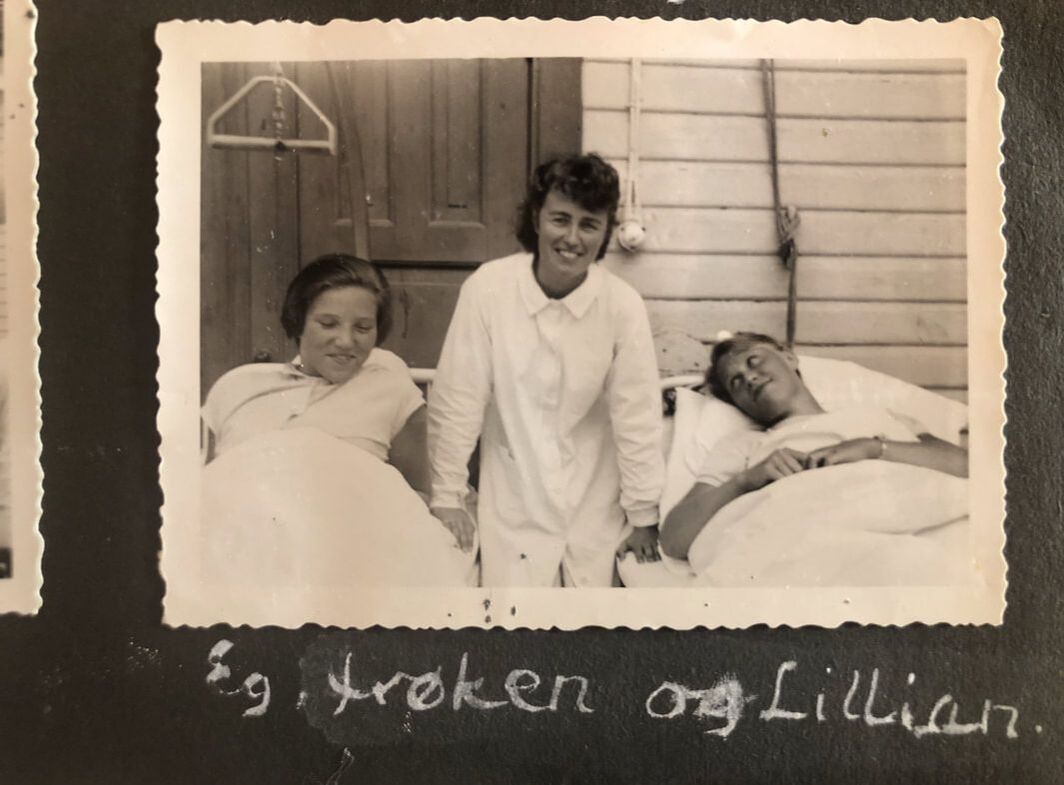

Kysthospitalet (coastal hospital) where Karen spent much of her childhood primarily treated patients orthopedically, and all of Karen's bone surgeries happened at this hospital. The final operation on Karen's right leg caused Karen's knee to buckle backwards. That is when she stopped going to Kystha.

My mother also understood that her mother’s way of dealing with the gender roles, binaries, and power dynamics in her parents’ marriage, her mother’s kind of womanhood, needed to change in her own marriage, for the sake of her daughters, and for her own sake. And my mother needed a powerful tool fueled by love to make that change. My mother chose to co-live.

~ Karen ~

In 2020, I was interviewed by my dear and good friend Lynn Rose for her podcast for the American University of Iraq about my experiences with disability and gender. The interview explores some of how I figured out that I needed to do gender differently from my mother and from the rest of the world. A link to the podcast is posted below.

The whole podcast could be listened to right now before reading on. The interview is about 50 minutes long. Or, the podcast could be skipped for now, and maybe come back to later. Listening to this interview won't be necessary for understanding the rest of this section.

To listen to the entire podcast, go to this web address: https://soundcloud.com/auis/lynn-rose-speaks-to-karen-hagrup

Before becoming a mother, as a special education teacher, I wanted to be with the kids and share questions, experiences, and activities, rather than lecturing or commanding or scolding. Even as a teacher for deaf-blind, profoundly retarded, autistic rubella children, I learned to use a program called co-active movements to see if they could learn to relate to people or events.

By now I understand co-living as having to do with being in an intimate relationship and sharing life experiences, especially all the challenges and benefits of growing old in a non-heternormative partnership. It is much more reciprocal, learning from each other and finding comfortable ways to accommodate each other, while also maintaining healthy boundaries.

Karen’s story joins the twentieth-century U.S. disability rights rallying cry, “For people with disabilities, by people with disabilities!” by purposefully deploying a co-living narrative voice, what linguistics nerds call the middle voice.

As you may have guessed already, the middle voice is not particularly common to English, and only somewhat more common in Norwegian. So while the sections, paragraphs, and sentences of Karen’s story are clearly written in more common active and passive constructions that are common to English, we have aimed to make the overall voice of the text somewhere between doer and receiver, or rather and as much as possible both doer and receiver.

~ Karen ~

This idea of “for and by people with disabilities” is based on the independent living movement and the political aspect of that. Before the independent living movement, services for disabled people were handled by professionals or experts who were in charge of making decisions, and those decisions were enforced by policies that were not written or created by disabled people.

Everywhere in human history, disabled people have lived with nondisabled people. At the same time, there is no single story of disability, no one narrative that explains what disability is. Many disabled people have worked together in many different ways to stay alive, to adapt the world to their needs, and to claim recognition for their experiences. My mother is claiming her boundaries all the time, claiming her multiple truths.

Throughout the story, we mindfully explore multiple nonbinaries, rejecting this-versus-that constructions. Rather, as writer Todd Pittinsky argues in his book, Us Plus Them, we gather in multiple ways of storytelling, and we view all of these ways of storytelling as additive. We also believe that this pluralistic, third voice supports sharing responsibility, as well as breaking down and breaking free from strict roles.

As a young person, Karen rode on her sister’s bike to school and was driven around by male adults. Later, as a disabled woman, after Karen learned to drive she became the main driver in her world, driving well before her husband was a driver, and continuing to be the main driver in her family throughout her marriage. And even later after that, as Karen’s wet macular degeneration progressed, she began again to rely on someone, BJ, her female life partner, to drive her home from doctor visits. Karen's driving journey blurs gender and disability lines from a black-and-white narrative about who is the driver and who is driven.

In this way, the co-living voice of this story is also a response to sexism and to ableist sexism in particular, through co-empowerment. Karen and BJ are empowered by themselves and each other. They are both doers and receivers of power.

~ Karen ~

You know, even before I knew about the independent living movement, I was disturbed by the behaviorist view of education where the teacher was in charge. That offended me big time.

In Norwegian, the word for teaching and the word for learning is the same: lære. I teach you, you learn, You teach me, I’m learning, you’re learning — they’re all the same word. The sentence “Jeg lærer,” can be translated as both I’m learning and I’m teaching myself.

~ Anna ~

That’s cool, mom. I love that Norwegian works that way.

~ Karen ~

Me too.

~ MWe ~

MWe three?

~ Anna ~

And yet, we must acknowledge that at times neither I nor my mother exist in the marginalia of nonbinary co-living, where neither of us are marginalized by gender standards. While I identify as genderqueer, I often present as feminine. Karen identifies as a cis woman. Outwardly, both of us hold some space at the center of the page regarding gender because neither of us are as marginalized as folx with nonbinary and trans identities.

~ Karen ~

Yes, but Anna, you are really saying something important here. You are showing how my story belongs. It’s not the most important story. And it’s not unimportant either. My story belongs to history.

~ MWe ~

The story tells itself because no one person owns the story. The story is the historical record and the perceptible truth. The story is the result of the action and is also the action. It’s both what happened and how it happened. In this space of truth that is universal and shared, the characters tap into both action and reaction, to a place where they both participate and observe, and to a home and a society where there is mutuality in the way the story unfolds.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed