(plural. compound noun.) words used by your immigrant mother as a substitute for direct connection to the parents, sisters, and friends she left behind; expressions and conceptual thinking that helps her deal with the separation; typically exclamations, puns, and attributions

An ability to stay safe by knowing how to talk to one person in one context, like a teacher at school, and how to then talk differently in another context, such as to a parent, a clerk at the grocery store, or a police officer, is sometimes called code switching. In addition to keeping people safe, code switching can also help people regulate their nervous systems and feel secure in different situations through the use of language. Translating words from one language to another is an additional way people regulate their sense of security.

Have you ever noticed someone who is speaking a second language and then suddenly exclaims something in their first language? They might be excited, joyful, afraid, or angry. Regardless of the emotional response, it’s possible that they are also having a nervous system reaction in that moment. Those first-language words can help the person come back to a familiar pattern of thinking from childhood, and help create ease or calm or a sense of control or stability in a tricky or intense moment or situation.

People can also gain a sense of security from connecting the differing meanings or cultural nuance of words and tone across settings or languages, or for that matter, from leaving behind unwanted meaning. And a felt sense of security is gained through the process, through the active effort of changing and reworking language. For my mother, learning English and acclimating to the cultural context of an English-speaking country literally rewired her brain. She was able at a neural level to transition her attachment by using a new label for the same object, repeatedly, until her brain was used to describing and redescribing objects and foods that gave her a sense of purpose and connection from one location to another. In some cases, hanging on to the original Norwegian and simply inserting Norwegian words into her daily life was particularly transitional and supportive for Karen’s safe transition to the United States. Krumkake (waffle cookies), bestemor and bestefar (grandmother and grandfather), ja vell ja! (yes, well, yes) — these and more were words and expressions that I grew up with and that felt to me as ordinary as their English counterparts.

For this reason, Karen's story has an international diction or word choice. You will see translations of words throughout the writing. These translations indicate words that helped Karen transition her secure attachment in one context, Norway, to secure attachment in another context, the United States. Many people use transitional objects and foodways to do this, and many people who emigrate, immigrate, and migrate, by desire and by necessity, transition their sense of security in the world through language.

Karen’s transitional words are not transitional objects in the sense described by well-known psychologist Donald Winnicott, but rather ways of speaking, concepts, and thought patterns that have a range of meanings and mysteries to unpack. Here in the language of what we’re calling transitional watchamacallits, a word my grandmother on my father’s side, Karen's mother-in-law, brought into our family culture, Karen has found comfort in her thinking power, her power to imagine. What after all is a watchamacallit? It’s a made-up word that is not exactly “what you may call it,” but that simultaneously conveys a sense of something hard to define, yet needing definition nonetheless, something to identify with — you know, a watchamacallit.

Part of Karen’s joy and security in life, both in Norway and in the United States, has always lived in her sense of humor, and especially in puns. Humor just makes sense as a place of beauty in the margin. Humor is a core battle cry in taking a stand for our joy in the face of oppression. For Karen, puns that work across language, or jokes that are funny in one language and not another, or just being able to express humor in a new language — these are all ways that Karen helped herself to stay connected to others and to manage those early cross-cultural connections, and in turn to hold onto her happiness during a turbulent time of transition in her life.

In 2016, Régine Debrosse wrote,

Belonging to several cultural groups at the same time can be associated with complex feelings of group membership . . . many immigrants marginalize — feel detached from the mainstream culture they live in and the heritage culture they grew up in — while feeling happy.

For Karen, being a thinker from childhood was a core part of her identity, something she could just know she was good at without question. At the same time, Karen’s translations, word choices, and puns and jokes decentralize power from those speaking a single dominant language and create shared authority across multiple languages and at the site of Karen’s own knowledge base. This shared power has allowed Karen to access a more fluid meaning-making process in the wider margins and in the margins of Karen’s own heart and soul.

In this way, the transitional whatchamacallit translations and word choice of this story is also a response to anti-immigrant policies, attitudes, and violence through homegrown, people-powered cultural reclamation and syncretization.

~ Karen ~

You know that when I turned twenty, my twin sister turned . . .

~ Anna ~

My mother loves this joke so much. It doesn’t work as well in written form.

~ Karen ~

Twenty too!

~ Anna ~

It sounds like twenty-two, t-w-o. And that doesn’t make any sense since they’re twins.

This pun doesn’t work in Norwegian. My mother told this pun probably literally hundreds of times just since I’ve been old enough to understand it, maybe hundreds more before then.

~ Karen ~

And when I turned thirty, my twin turned . . . And when I turned forty . . .

I have been learning Spanish my whole life. I’ve studied in the classroom since I was a teenager, as well as traveling to Spanish-speaking countries. Still, I have not gotten fluent. But sometimes I dream in Spanish. In these dreams, I make contact with the way the brain can flexibly use multiple languages to wire and rewire one’s own automatic thinking. I wake from these dreams, typically, feeling serene at first, and then astounded. I can understand how unconscious feelings can migrate around in us through language.

In Ezra Klein’s 2019 podcast “We don’t just feel emotions. We make them,” Lisa Feldman Barrett explains how having a word for a set of sensations and information coming through the senses to the brain both gives rise to the experience we call emotion and helps shape that experience. For example, telling a kid, "Oh, you're crying; you are sad," can help that kid feel sad again in the future because they have a word now for what they were feeling, and that kid may even feel sad more often or more intensely. In some languages where there is a word for an experience, a concept for that experience feels natural. In other languages where there is not a word for the same sociophysiological experience, the same concept can feel foreign and even incomprehensible.

On many fronts, language conducts a ton of energy, information, meaning, and impact. In the telling of Karen's story, we attempt to be mindful of the impact language can have on connecting us to or disconnecting us from the margins.

As such, it's vital to acknowledge that all of the languages in this story are languages of people and groups that have conquered, dominated, or committed violence against other groups. English, Norwegian, Spanish, and Hebrew. Additionally, Karen has not been regularly speaking or thinking in Norwegian for many years by now, and the vast majority of this story is being written in English, the only language that I speak fluently.

On the phone, Karen tells me,

I’m going through my papers. Throwing things out that are duplicates or not important to me. Two big containers of photographs. I would like to go through some of this with you. I threw away many letters from Sigrid. I don’t need to know all about all of her boyfriends. I threw out quite a few of my twin sister’s letters. She sent me so many letters that started, “I am continuing the tradition of writing Christmas letters from Sweden.” It usually was about some thing where they went shopping, or house care, or meeting with friends. Haldis never wrote deep insights into anything really. Some letters were about how she had been preaching, but she didn’t say much about what she said. Some of the letters I’m keeping because they’re more substantive. But they’re all in Norwegian. And I’m keeping a few letters from my mother, too. And they’re all in Norwegian, too. It feels like I’m freeing myself from this compulsive idea to hold onto everything that came from Norway. It’s a little less obsessive.

In the face of her surrender, I press on, asking her to write down more of what she remembers. I write a question on the computer — linked in real time by the magic of the Internet — for her to look at and respond to miles and miles away from me.

What are some of your favorite words or sayings in Norwegian?

~ Karen ~

I live my life in English now, and most of the Norwegian words that come to mind tend to block my ability to come up with the appropriate English word for the moment. To answer this question, I would have to do some deep thinking.

~ Anna ~

I keep pushing us forward, typing more questions to her.

Do you have favorite Norwegian artists, writers, and thinkers? Who are they and what did they show you?

I wait. I breathe softly with her over the phone. She breathes with me.

And the flood gates open.

~ Karen ~

The the first books I read that described in a sensitive and realistic way what it is like to be in love and have sex were Sigrid Unset’s trilogy, Kristin Lavrandsdatter. I lived and taught in Grimstad at that time. Undset was born in Denmark, but her family moved to Norway when she was two years old.

When I was younger I was moved by Knut Hamsun’s description in Markens Grøde (Growth of the Soil) of how Norwegians during past centuries cultivated, farmed, and lived off the scrappy land. I've heard much later that he was a nazi.

I brought a book by Jens Smedslund with me from Norway to the United States. The book described his research with children that built on Piaget. I no longer have that book, and I cannot find it in his list of publications, but there is an article that I think is covering the same topics: “The Acquisition of Conservation of Substance and Weight in Children. VI. Practice on Continuous Versus Noncontinuous Material in Conflict Situations without Reinforcement.”

Inger Hagerup’s Lille Persille has fun poems for children. There are a few I translated years ago.

Whenever Edward Grieg’s music comes up on our TV station for classical music, BJ turns up the sound really loud, especially if I do not happen to be right there. Ingrid Espelid Hovig was a Norwegian television chef and wrote cook books as well. Her signature phrase after finishing a recipe was, “og litt grønt på toppen” (“and a little green on the top”). While attending Spesiallærerskolen (special education teacher training) in Oslo, I lived with Haldis near the Edvard Munch museum. I loved his paintings, especially The Scream and The Day After. I love this description from the Smithsonian on Munch's work: “Edvard Munch, who never married, called his paintings his children and hated to be separated from them.” I loved to listen to Alf Prøysen’s music, especially early in my stay in the U.S. At times when Jerry and I were fighting, I would sit in my bed and play his music loudly to drown out whatever Jerry was saying. During the year that I stayed in Oslo with Aslaug and Petter Kirkevold to get treatment for my polio leg, they took me to see a show by Sonja Henie. I got to sit right next to the ice rink. I was so close that I could almost touch some of the big feathers she wore and swung around. I felt proud to be from the same country as explorers like Fridtjof Nansen and Roald Amundsen.

~ Anna ~

My mother loves her twinkle lights. She wants to look at art she painted and hold objects in her hands that she brought with her from Norway. She was enamored of a gadget that swiveled open with multiple hooks to hang coats on that you could attached to a door or wall, and was pained to see it go to Goodwill when neither my sister nor I felt compelled to keep it.

But she is also deeply committed to the news and to looking at the headlines that come to her over her cell phone. She seeks intellectual stimulation automatically. I get it. So much of my identity is also built from my sense that I'm smart, that I have interesting ideas.

Perhaps, I muse, Karen's cell phone may be a meeting of transitional object and transitional whatchamacallit. Margaret Hefferman has said that, "The cell phone has become the adult’s transitional object, replacing the toddler’s teddy bear for comfort and a sense of belonging.” But my mother never ceases to find meaning through her phone. In 2022, Karen looks up from her cell phone at me late one night while I sit by her bed handing her a bottle of ginger ale for the nausea, and says with awe in her voice, "There's a . . . what's it called?" She pauses. She is pausing more and more. This one is a long pause; I start looking at my own phone. "Meteor. That's the word. There's a meteor shower coming. Isn't that cool?"

And still, I have more questions.

Do you have Norwegians who you disagreed with? What did they think? And what did you think?

~ Karen ~

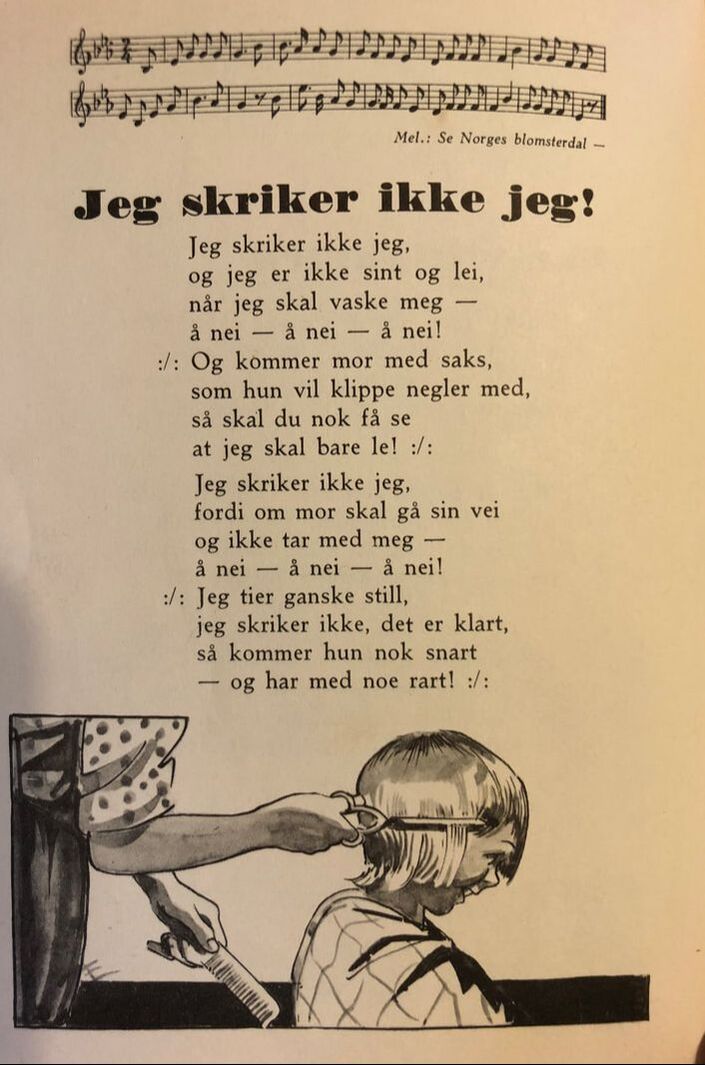

I still have this book, Kom Skal Vi Synge (Come Let Us Sing), by Margrethe Munthe that contains a number of children’s songs. My mother loved this book because she liked the ideas expressed in the songs. Children should above all be compliant and calm. Children should not be defiant or loud. Children better not be angry because if they were angry too often, nobody would love them. When I became the mother of two daughters, my expectations contradicted my mother’s in just about every way. We did that co-living thing. (See previous section.)

And I think I should also talk about this one other book that my mother used to read for the youth group out loud. The one about gypsies, a word I know now is derogatory. At the time, the way my mother read that book, well, it became sort of dramatic. I didn’t have very many misgivings about it at all until much later. But it was a very important thing for my mother to convey how if you are an upright believing Christian it shows up in your life and in your children. This is what set Christians and gypsies apart in my mother's worldview. And the fact that Haldis still has that book — I don’t think she has any misgivings about it yet.

I suppose . . . I suppose you could include my mother, too, in the people whose ideas I disagreed with eventually. The Kristin Lavrandsdatter trilogy was such a stark contrast to the books my mother had encouraged me to read. Some books had a young girl who was totally passive and waiting for a nice guy out in the world doing who knows what to come back and decide to marry her. And the woman’s role in my mother’s mind was essentially passive.

~ Anna ~

I can feel the heavy sludge of childhood trauma creep over Karen as she falls quiet for a moment. The sludge creeps over both of us.

~ Karen ~

Especially me.

It was like my mother was waiting for someone to choose me.

And yet clearly I wasn’t eligible to be chosen because of my disability. She really wanted for me to be perfectly passive and somehow chosen, even while she didn't believe that would ever happen.

So I’d like to add something like that to the book. That the Lavrandsdatter trilogy was the first description of a sensitive way to be in love and have sex that I had ever read; I had never been reading that anywhere before. The things I was encouraged to read were so based on my mother’s idea of the kind of life she expected me to have.

Jeg skriker ikke jeg!

Jeg skriker ikke jeg,

og jeg er ikke sint og lei,

når jeg skal vaske meg --

å nei — å nei — å nei!

Og kommer mor med saks,

som hun vil klippe negler med,

så skal du nok få se

at jeg skal bare le!

Jeg skriker ikke jeg,

fordi om mor skal gå sin vei

og ikke tar med meg --

å nei — å nei — å nei!

Jeg tier ganske still,

jeg skriker ikke, det er klart,

så kommer hun nok snart

— og har med noe rart!

(I'm not screaming!

I'm not screaming,

and I'm not angry and bored

when I wash myself --

oh no — oh no — oh no!

And if mother comes with scissors,

which she will cut nails with,

then you will probably see

that I will just laugh!

I'm not screaming,

because if mom's going her way

and not taking me --

oh no -- oh no -- oh no!

I'm pretty quiet,

I'm not screaming,

of course, she's probably coming soon

— and has something strange!)]

Tell me anything else you want to about language. Anything at all.

~ Karen ~

When I first started living with my children, I was also living with your father, Jerry. Language was an important issue in several ways. I decided not to teach my daughters Norwegian, even though I knew that growing up bilingual was an advantage for kids who could handle that. Because I had visited Norway with Jerry, and we had spent time with people who spoke Norwegian, I knew that the politics within our family would not be comfortable if the kids and I were able to communicate in a language he could not understand.

Jerry and his family were extremely verbal, and I was still learning to fully express myself in English. Our first daughter, Riina, did not start walking until she was fifteen months old, but started calling me Mama when she was about six months old.

Karen: What words do you remember making up as a kid?

Riina: Peba. That meant pick me up. I think I was also committed to saying poon instead of spoon.

Karen: When in the house Grandma, your father’s mother, bought for us and you were three or four years old, you were out on the patio one day walking around, and you were talking and talking and talking in words that nobody understood. Language was just pouring out of you.

Riina: That’s the story of my whole wide life.

Karen: Was it difficult for you ever to grow up with an immigrant mother with a disability?

Riina: It was annoying when I was ten and we would go shopping and people would ask me questions. I was like, dude, I’m the kid. Ask my mom.

Karen: Kids didn’t make snide comments?

Riina: I was a big enough nerd that they would just make fun of me directly.

Karen: Were you ever ashamed around me?

Riina: No.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed