My mother and I have spent a lot of time over the years reflecting on our differences — the ways we each feel different from mainstream culture. Lately, we have spent more time thinking about and telling stories about how we are the same as many culturally dominant groups. We have been able to talk with each other in this way between us. We have gotten committed to telling the story of the range of privileged and oppressed spaces we occupy collectively.

It gets murky fast, and overly conceptual. My tendency is to go high up in the clouds.

I keep committing to the process.

It feels necessary.

Necessary, also, because the stories we’ve told to each other about ourselves over the years are always changing. As illustrator Leah Pearlman writes, honesty is the only thing that can keep up with change. Here’s a little honesty about my younger self and how I have held and defined my mother in the past. In my early twenties, I began writing about my family for various graduate school writing projects. I sense that I was not as good at honesty back then, and I’m still working on opening the door to my whole truth. But now I’m stalling. Let me get back to the honest part. This is how I described my mother in the opening paragraph of one essay:

When my mother was three years old she ran through a muddy field and came home with polio. I like to imagine her this way, 1945, rural Norway, north of the arctic circle, a three-year-old child with ridiculously dark brown hair running fast, as fast as her baby legs can carry her — alone — through a field of heather and cloudberries. Coming closer I can almost see the polio fairy dust jump up out of the ground and sting her bare feet. She winces in pain. Her right leg goes limp. At the same time I see that she is no longer a child. Turning fast into an adult, her leg has stopped growing with the rest of her. She pauses in the field for a moment while a large metal brace wraps and buckles around the short leg. But she doesn’t stop for long. She moves forward again, walking now on crutches. Too slow! She pushes forward in a manual wheelchair. Still, too slow. Finally, she surges toward me in a battery-powered chair. I like thinking of my mother as a crippled Norwegian goddess descending from the far north, hitching herself to a star, and crossing the Atlantic Ocean on a winged chariot of metal to find my father in small-town Ohio.

Necessary, also, because today I am trying again to see more of my mother, to not obfuscate her with my daydreams.

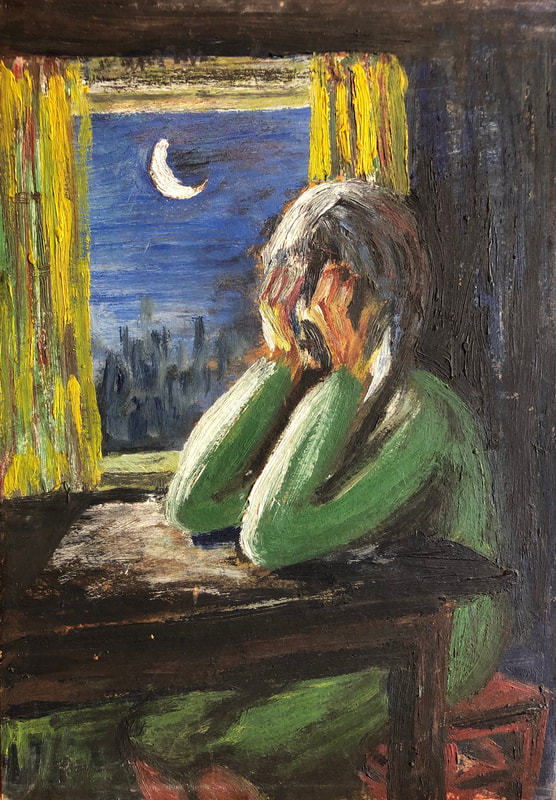

My mother’s names have been Karen Magnhild Nygaard, Karen Nygaard Hirsch, and Karen Hagrup. She was born in 1942. She was born in Norway and immigrated to the United States. She’s white. She’s a cis woman and uses she pronouns. She’s a twin. She is one of four sisters. She is lovingly partnered for many years to a woman, after a long marriage with a man. She says now that she must be bisexual. She got polio when she was three, has grappled with years of post-polio syndrome, and in her older years is navigating wet macular degeneration in both of her eyes. She has herpes and a thyroid imbalance. She has been taking Wellbutrin for over a decade. She is retired and lives frugally on what she has. She has been a teacher, a professor, an executive director, and a founder. She is a writer and an artist. She hates violence in movies. And she loves color and lights.

All of these parts of her have beginnings that lead to longer stories. And all of these parts of her have been the perfect mishmash all together to feel like she has not just been marginal to society, pushed out of the center, but that instead she comes from somewhere completely other — somewhere beyond the margin.

For at least a couple of reasons, my mother imagined herself living off the edge of the world well into her twenties. When she was a child she traveled with her father to a Norwegian island called Skorpa where one family lived so that her father could minister to that family. Skorpa means crust. Traveling through stormy, isolated landscapes like these was common in my mother’s childhood. She grew up believing that Norway wasn’t totally part of the world, that the action must be other places. Some of her time spent with her father included traveling to rural homesteads and him showing his daughter and her polio leg off to adherents as testimony of god’s power and mercy. She sensed for many years that her parents already imagined her residing in paradise, not fit for life on earth. Growing up, my mother didn’t have the language of marginalization or an identity as being part of a minority group, something that would put her somewhere on the map, if only at the outskirts. As a little girl my mother understood her place in the world as somewhere not totally in the world.

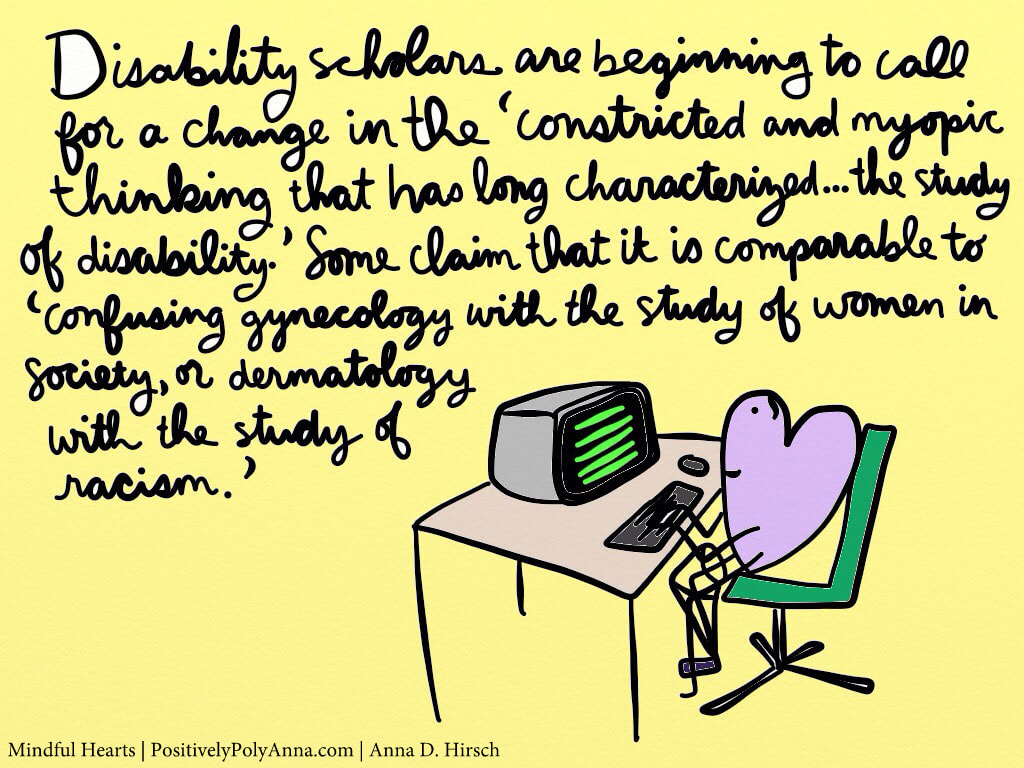

At age twenty-seven she decided to leave the crust of the world behind her. After many years receiving messages that her life belonged to her parents and to god, Karen crossed an ocean, got married, raised two children, and had a prolific career. In the eighties and nineties, my mother was one of the first people to tell the world that disability is a cultural and political experience, not just a medical one.

Today she often still feels that her voice and contribution has already been forgotten in the wider disability culture. She has a doctorate, offered her own life toward winning through settlement an early legal case under the Americans with Disabilities Act, has met Barack Obama three times in the course of helping him get elected twice, and still often feels unaccomplished. My mother is a female disabled immigrant whose writing hasn’t been published nearly enough, nor as often as my father’s writing has been.

My mother speaks two languages fluently, and sometimes when she opens her mouth she feels like she can’t say anything anyone will understand. She is really good at laughing at herself at times like these, and her own shy but resilient sense of humor, teetering between despair and joy, has certainly saved her and her nervous system from collapse for decades.

My mother knows things about being outside the in crowd. She knows what it’s like to work incredibly hard to get people to pay attention to you and often have the attention she can get turn into pity or scorn or revulsion. She knows what it’s like to internalize that kind of hurtful attention and end up working hard to hide oneself from others, from the world, from her own self-love.

She knows the unique challenge of trying to make it from the edge of the world into the margins of society. There is a language piece here, and a social and cultural piece, as well. Margin and marginalization were words and concepts that my mother got when she learned English and moved to the United States in her late twenties. She did have access to many advantages and centering experiences as a white European Christian with financial stability, including accessing the Independent Living Movement and other disability rights communities in the United States, which gave her a political and personal context to flourish, to become conscious of her marginalization as a disabled person, and of her privilege as well. Even with all of this access and with all the talk of centering her experience, my mother knows that she may never actually get to the center. The center was not built for her. Frankly, it’s no longer where she wants to be anyway.

Still, my mother asked me to help tell the world the story of her life. She asked me to use my privilege to help center her. I said yes.

I also asked my mother what she thought about the idea of inviting people to meet her in the margin instead. I asked her if there was magic there that people needed to know about, experiences like my Judaism and her disability. I asked her if the margin, after all her years, was a good place. She said yes.

We have made each other think. Hard. And a lot.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed