In most books the margin is a blank white, open, and seemingly unstructured space. Yet there is a kind of a structure to the margin of printed texts. You can see some of this structure more clearly where someone has passionately scribbled a note along the side of the page, perhaps arguing with the author, or perhaps as a reminder to themselves to come back here. But sometimes what happens in the margin has less and less to do directly with the center of the page. Sometimes we are lucky enough to notice that the margin is its own world.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the way my mother’s creativity, thinking, and writing has never stopped, no matter how marginalized she has been, by her family and by society. She has endlessly looked for new ways to solve situations and bring more color and new insight to basically everything she touches. And she has long known this about herself. But she hasn’t had a word for this drive in her until I suggested one.

Marginalia.

I like this word. I like the word marginalia in a similar way that I like the word marginalized and the framework each word can offer in seeing our marginal experiences. The 1960s concept of social marginalization helped generations after confront a world that was good at pushing many people and groups to the edges of society. Since then many have worked to center people’s marginalized stories in order to achieve social change. But the center is, well, still the center.

While having drinks with a social change agitator, this friend and colleague reflected to me that the fame and notoriety of some of her peers and their entry into mainstream prominence was troubling to her. She wasn’t sure how their newfound followings were creating foundational change for the people they intended to be standing up for — and, supposedly, with. She wondered if in the process of a few breaking through many, many more were leaving people behind in the margin in the same old, familiar ways. I told her that I was riding that tension myself, wanting my mother’s story to get out there, wanting to be well-known, and knowing that meant my mother could become subsumed by a kind of royalty-making of a handful of now somehow elite marginalized experiences. I told my colleague that my mother and I wanted to do something different, to invite the world to do something different. I shared how I was unsure of myself in that process, but that I suspected that maybe the difference could have something to do with distrusting the center.

In writing about the margin and following my intuition, I am taking a leap of faith. I don’t know where the pieces will fall. And I’m pushing my mother along with me. I worry that like the time I once pushed her too fast in her manual wheelchair and hit a bump and toppled her to the ground that I may topple her identity out onto the page. I check in with her often in hopes that we can make this leap together and find out the impact of our actions and of her life while holding each other’s hearts with care.

I turned to my colleague and I declared that what happens in the margin matters, has always mattered, and will always matter. Period. My colleague nodded and said she wanted to hear more. I breathed out. I think I could feel my mother’s tightness, her anxiety about mattering, in my own body.

Getting curious about the word marginalia has led me to others who share a similar curiosity in this edge work. In 2019, Vernon Press published a multi-authored volume of collected essays that “immerses us into the fertile ground of the ‘margin’ and its fluid and porous relation to the ‘centre’ across history.” Shortly after, also in 2019, Benjamin Wild gave a TEDxSherborne talk titled “The Magnificence of Marginality.” And in 2018, Jacqui Palumbo took another look at the art and work of Diane Arbus, known for using photography to normalize marginalized groups. Arbus herself wrote, “In a way, this scrutiny has to do with not evading facts, not evading what it really looks like.” Edge work itself, the work of uncovering and uplifting what happens in the margin, often exists at the edge of mainstream thinking, writing, and art and at the periphery of mainstream living.

Well into the middle of her life, after giving birth to me and my sister and many years of raising us, my mother was still operating on and modeling for me and my sister her struggle with an internalized but uncomfortable lesson that you are more interesting or worthy when you are in the limelight. She believed that centered and visible text was the only writing and storytelling that could clearly and effectively communicate complexity in this world, and possibly, she worried deep down, the only text that mattered.

As I reread the opening of the essay she started in 2005 for a collection of essays on disability in the field of education that she was invited to contribute to, I listen deeply to her literary voice. Her perspective as a doctorate of education was imbued with a lifetime of deep curiosity about the intersection of disability and culture and its effect on learning and development. Her essay was never finished and the writing she did for this collection was never published. Eventually the collection was completed under the title Disability and the Politics of Education: An International Reader. When I look through the table of contents I worry that the book that was published is too center-of-the-road academic. That it missed an opportunity to catch the ordinary joy of everyday humans, writing in everyday language, in favor of academic-ese. I regret that my mother’s straight talk is not there to remind us all that academic centering can also be a dangerous proposition for people with disabilities and for immigrants.

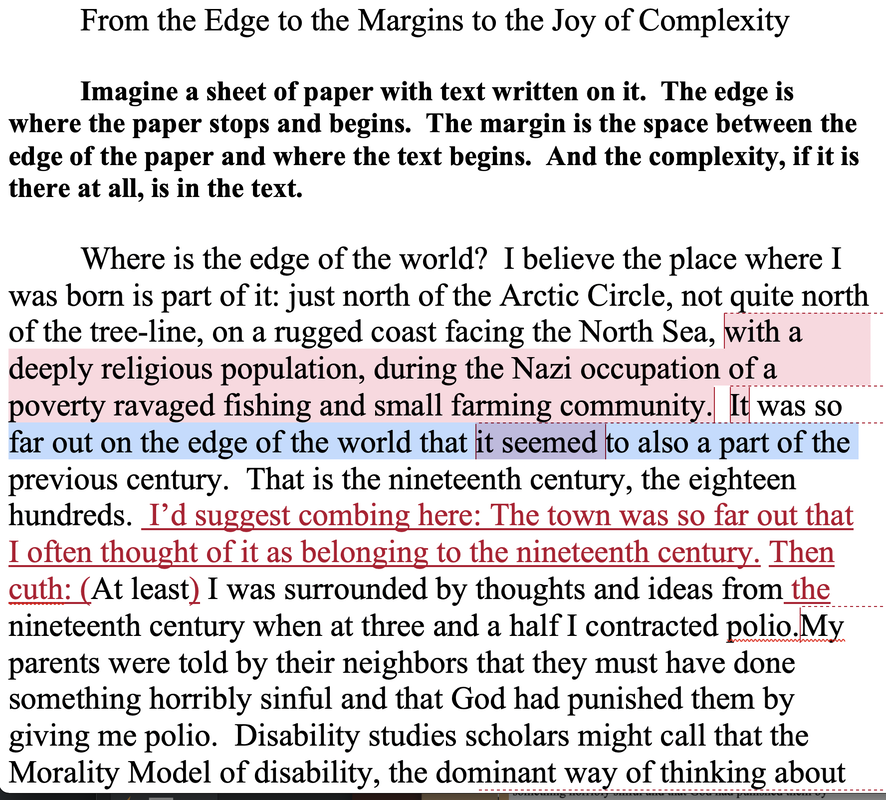

(c. 2005) Imagine a sheet of paper with text written on it. The edge is where the paper stops and begins. The margin is the space between the edge of the paper and where the text begins. And the complexity, if it is there at all, is in the text.

In many ways, my mother has always been happening in the margin.

(c. 2005) Where is the edge of the world? I believe the place where I was born is part of it: just north of the Arctic Circle, not quite north of the tree line, on a rugged coast facing the North Sea.

And in many ways, like Frida who she adored, my mother has always been painting her own reality — in the margin. She had to, of course. But she also did so with candor.

(c. 2005) The poverty ravaged fishing and farming community was home to a deeply religious population and was occupied by the Nazis during World War II. The town was so far out on the edge of the world that I have often thought of it as belonging to the nineteenth century. I surely was surrounded by thoughts and ideas from the nineteenth century when at three and a half I contracted polio. My parents were told by their neighbors that they must have done something horribly sinful and that God had punished them by giving me polio.

When my mother wrote this essay in 2005 she was still trying to center her voice by fitting into other people’s boxes — in academia, within her family, on the written page. In a world that had marginalized her for decades, she understood that the complexity of life was only widely visible to others at the center of the page. She was trying to get to the middle; she was trying to be seen. But the meaning of her life, perhaps hidden to others, the pieces of meaning embedded in her having been asked to submit a chapter for a book never to hear back again on its publication, my clumsy attempt to support her English grammar, her life story edited down to several pages of stark, true, and inadequate sentences about her life’s journey so far — these bits of very big meaning were there all along in the margins, unfolding rapidly and beautifully and mysteriously. Her story is not a center-of-the-road story. In fact, she had to fight her way from the edge of the world (northern Norway) into a mainstream setting (the United States) in order to gain a marginalized identity (disabled and proud).

And that is where I want to meet her — still encoding the meaning of her life in the marginalia, the creative content that my mother is still making for herself around the center of the page.

She sits in her condo in St. Louis looking at her hummingbird feeder and waiting for the hummingbirds to arrive for the year because it brings her joy, while also contemplating if she did enough as a disabled person to change the world for other disabled people and why it has been so hard for her to get noticed for what she did do.

I am here sticking it out with her, holding her in my certainty that she does matter and that her story matters. I am dedicated to telling a story that belongs to someone who has been dedicated to me and my growth and my joy my whole life.

On days when I visit and we write together, she goes through her old papers again, trying to figure out what to throw away. Which poem is an important footnote to her childhood? Which drawing deserves an asterisk? Which ideas merit further definition?

I am a white, nondisabled person with an increasing range of lived experience. But I carry a lot of middle-of-the-road privilege and I can still sometimes forget how much everything always changes and be rapidly humbled again by a personal tragedy. Still, my writing lives more and more in the middle of the page, and my mother knows it.

When she asked me to help her write the story of her life, she knew that I could get her onto the center of the page where people could see her. I can and I will work for her toward that goal for as long as she wants me to. But the center of the page is not her story. Her story lives in the marginalia of life. And our combined stories meet in the margin in several ways that are important to reading this book and to understanding her story.

After many deep conversations, my mother and I came up with some categories of marginalia that are important to how we live and to how this story is written.

All of these categories are offered as overarching concepts with some concrete implications. As we see it, the marginalia of Karen’s life story, and of our storytelling, include but are not limited to the structures in and around the main text and are summarized below. We will unpack these textual features in more depth in the following sections, in hopes of helping the reader be as ready as possible for the adventure of reading her story.

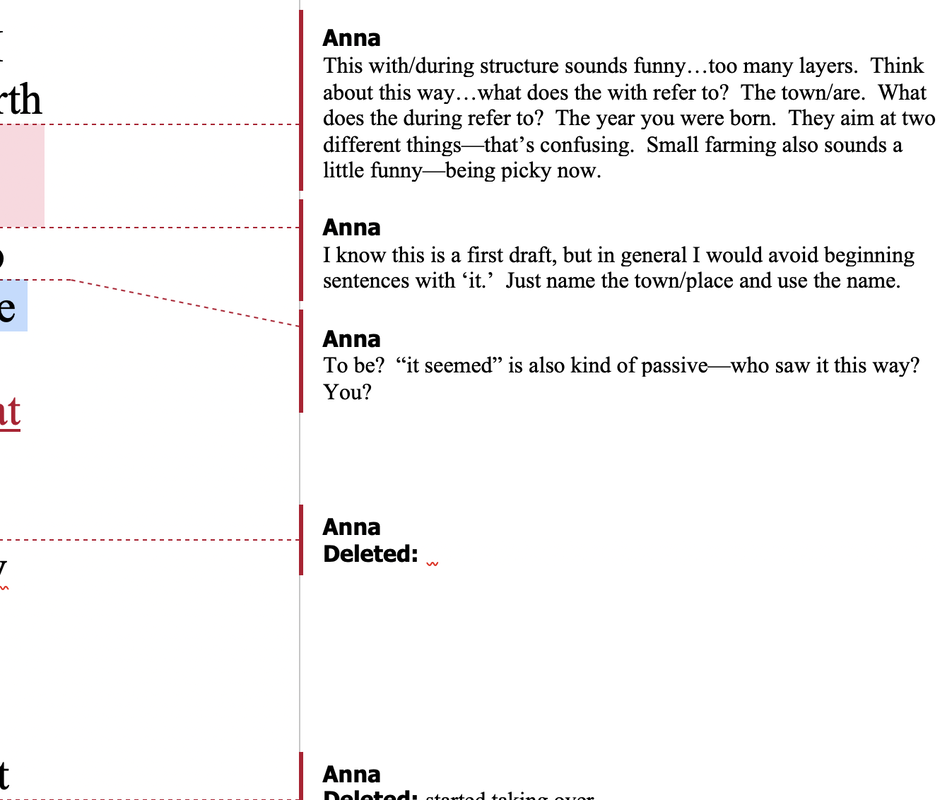

- Headers: The text includes headers that indicate the speaker. Sometimes the speaker is Karen and sometimes the speaker is Anna. And sometimes the speaker is a unique mixture of Karen’s and Anna’s perspective mingling with each other.

- Middle Voice: The prose style is intended to bring forward as much as possible something linguists call the middle voice. In the middle voice, the speaker is neither wholly active nor wholly passive, but somewhere in the middle. An example of middle voice prose is the story tells itself. The story both does and receives the action of the telling.

- Translations: The text also includes translations of significant words from Norwegian to English and from English to Norwegian that are important to telling the story.

- Questions: Questions are posed to the reader along the way to engage and inspire interactivity between the authors and readers.

- Story Sections, Timelines: The story will be broken into three Acts marking three periods in Karen’s life. Additional timelines will serve to help ground our nonlinear storytelling in linear time and place.

- Image Descriptions: Image descriptions and other access features are aimed at making the story accessible widely.

- Doodles, Illustrations, Pictures, Videos, Food Art: Images and sounds are added to give the reader a more immersive experience of the story.

- Sidebars: Sidebars throughout will offer historical and social context going on in the wider sphere at different times in Karen’s life journey.

- Diagrams: Diagrams will periodically offer interpersonal context, mapping the relationships in Karen’s story.

- Definitions: Definitions of concepts and ideas will be used to bring us together and go deeper in the meaning of Karen’s life.

- Footnotes: Data and references will create a bridge between Karen’s marginalized story and more mainstream parts of her experience and world.

As you read this story you will encounter a number of flourishes in our writing and storytelling style, many of which will be linked to the conceptual frameworks of the marginalia, as well as offering concrete learning aids. At any time when you are reading the story, you can come back here to review the meaning that we sense is embedded in these marginalia. We also hope that these marginal notes and embellishments are fun and helpful in making the journey of this story more vivid, interesting, interactive, and honest.

Have I ever told you that when I read texts as a younger person I would mark places I wanted to come back to with the letters NB in the margin, meaning nota bene, a note to myself to take special attention to that part? And then another little memory that comes back to me right now . . . this guy, Michael Avenatti, used to be on the news a lot because he was the one who dug up the story about the hush money Trump wanted to pay to keep a woman from speaking up about sex Trump had with her during his presidential campaign. So Avenatti, who was on the news a lot, used to say something that was fun for me to hear. He would make a point and then finish by saying "basta." It means period or end of story or can’t be argued with, something seriously ending or over. And that word is used in Norwegian, too. So that was fun for me to hear.

The marginalia of beginning and ending and <pausing> beginning again.

<laughing> Yes.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed