go FORWARD to Marginalia (part 6/12)

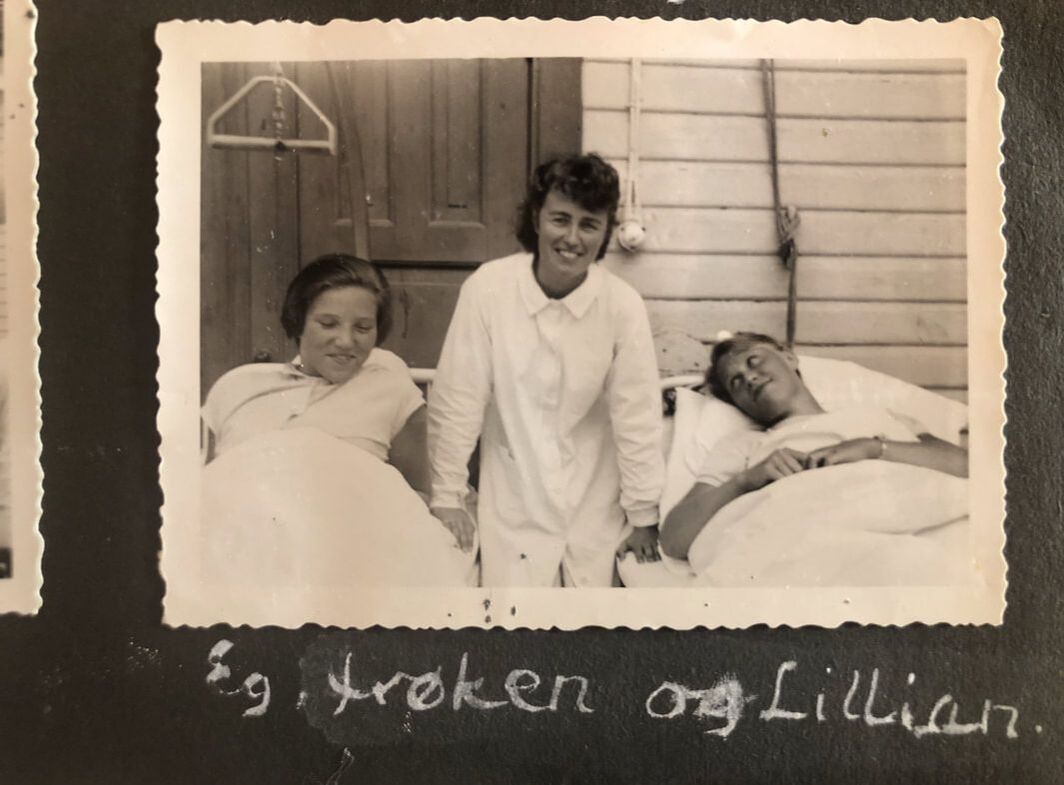

My mother’s story is love. An inclusive, non-grasping love. As her daughter, I have met her in this pedagogy of love a million times.

It is a pedagogy too often foreign to mainstream Western parenting theory, which is overrun with advice on compliance and success. My mother’s parenting theory? More love. Her life’s theory? Also love. Love defined further as the kind of nurturing love that frees the beloved, that does not cage. With her life partner, BJ, she calls this “growth for both.”

And in this field of love that my mother has cultivated throughout her life, she and I meet and learn from and teach each other — together.

We co-live.

What in the world is socioplasticity?

Socioplasticity is basically what it sounds like — it’s the plastic or malleable nature of societies at the macro level and all the way down to the micro level. It’s the changeability of any social relationship, community, or group of people. It's the ability of people who are co-living to be resilient together, to heal social harms and to flourish at the local level and globally.

In neuroscience, neuroplasticity is the ability of the brain to send information in new ways across the synaptic gap from one neuron to another neuron that has never made that particular synaptic leap before. Developing novel neural pathways is a critical element of learning, along with repetition of these new connections.

Similarly, people can invent new relationships and foster new depth and breadth in relationships and social networks across what Louis Cozolino calls the social synapse — person to person or brain to brain. And as information jumps from person to person in both familiar and surprising ways, over time we live out old wisdoms and simultaneously we teach ourselves new ways of being together.

Because Karen and I both understand her life story to be part of collective change, we therefore purposefully pose questions to the reader throughout the telling to support active, aware, and positive socioplasticity. This story in turn will have many different versions, as many versions as there are readers. And that’s how we think it should be. You are a critical part of how Karen’s story can help create positive change.

Arguably, socioplasticity as such is also just science jargon for what human rights organizers call social change. As we see it, socioplasticity is baked into being human, to being the social creatures that we are, but may often be automatic or unconscious, and too often a status quo reproduction of violent and damaging ways of being together.

But being in open connection and care with each other is possible if we can practice staying open and curious. In turn, we can bring more awareness and widespread positive outcomes to our socioplasticity by instilling in our social mapping and wiring and rewiring, both within our close-in circles and in our wider world, curiosity about self and other. And we can do that by asking more questions. And listening more deeply.

We can steer our social learning toward collective care.

Socioplasticity is therefore also a powerful tool for or means to social change. It offers a framework for influencing change in a particular direction through the cultivation of healthy, loving, mutually beneficial relationships.

Socioplasticity is also a critical aspect of being with intersectionality and intersectional social identities. We have to stop putting people in rigid boxes or categories and start listening to people’s truly lived and unique ways of being in the world. To do so, being curious with each other is critical. If intersectionality describes the particular experience of a set of intersecting social identities, socioplastisticity is a framework for moving intersectional experiences from siloed, intrapersonal expressions and separate spaces to collaborative, interpersonal conversations and shared spaces.

In modern life for a variety of reasons, we often put only parts of ourselves on display for each other. We utilize code switching or rely on cultural translations to keep us safe from oppressive systems, and even from each other. But there can be a cost we pay when we do this, and that cost is directly related to our own health and happiness. So we find our ways to show ourselves — our full selves — to someone, somewhere, a friend, a therapist, a stranger, if just for a moment, or for more than a moment; we find ways to let our deepest parts connect with others. Because that is what people do.

According to Barbara Fredrickson, love is more than a value or ethic, it is also a biological process and is actually quite conditional. It’s just that the conditions aren’t a thin waist and a fancy car. The conditions are safety, proximity, and physiological synchrony, like eye contact and breathing together, touch, dance, holding hands. In other words, love — wiring human-to-human connection — is the byproduct or experience of socioplasticity at work.

But in an oppressive world, when we hide part of ourselves as a protective response to oppression, we distance ourselves from each other. Literally, we create distance, segregation, gated neighborhoods, walls. This can feed into the recreation of even more fixed oppressive systems of separation, marriage inequality, prisons, deportation, caste. In creating all this distance we stop asking each other questions. And when we stop asking each other questions, we create more distance. We stop looking each other in the eye, stop sorting out time and space together, killing off our capacity for empathy. Ultimately we cut ourselves off from places and relationships for growing love and we weaken and starve our chances at incubating positive global impact.

There is, of course, nothing wrong with also relying on protection and self-protection as we need, as we find ways to connect. In many ways, protection is connection.

Using our boundaries and good judgment to find opportunities to show more of ourselves to each other in ways that actually work for us is vital. And yet through the practice of coming out to each other, mindfully, heartfully, and soulfully, at our right pace, we can change society and culture by rewiring the planet for love.

We can be in curiosity with each other, asking each other questions and really making an effort to more fully hear the unique and full answers we each bring.

While we are excited to bring forward more inquisitiveness, questions, and complexity, we know that Karen’s story and our storytelling can at times get focused on single issues, dragging us inexorably back toward the center of the page where things are more black and white, less gray and imaginative and intersectional and uniquely human. We know that at times we struggle to hold a flexible approach to making meaning out of the details, to letting Karen’s whole story and her whole self be present, to letting the wholeness of the reader engage with Karen’s whole world. At times, we clench, shield, push away, becoming incurious even with ourselves.

Like many or maybe most, shame and hiding are deeply trained in both of us. But where we can, our aim is to disrupt this pattern of hiding parts of our humanity. Our aim is to co-learn in a field of intersecting identities, love, and connection, within ourselves, with each other, and with you. In this way, the questions, the shared meaning-making, and the socioplasticity of this story are also a stand for intersectional lenses and learning.

What exactly is the experience of a white disabled immigrant? Do we know, Anna?

One Thursday on the phone, I’m talking to my mother more casually. I’m in some kind of mood.

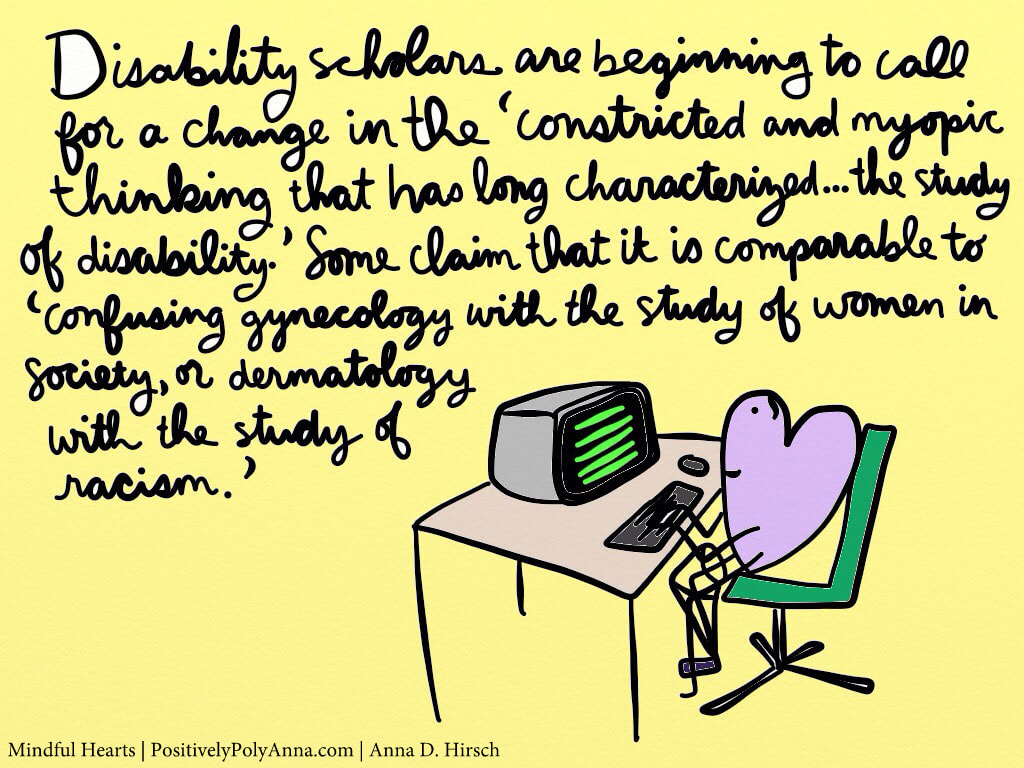

What I like about your story is that it is and it isn’t a polio memoir. It is, but it’s more than that, too. You’ve done so much around being gay and an Obama supporter and a disabled immigrant. You’ve attacked life at a lot of levels, simultaneously. You’ve had to. Your being in multiple ways and cultures in the world made it a point of survival for you. I listened to a podcast yesterday that I appreciated a lot, though I still have arguments with. It was about emotions and it was on the Ezra Klein show, an interview with Lisa Feldman Barrett who wrote How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. Barrett really argues against the assumption of loss and grief as natural, and how these processes are also cultural and not particularly or always freeing for people. Like my professor at the University of Chicago demanding that disability is loss. Period. Nothing else. Blech. You have known this for so long, that disability is cultural. You managed to have that thought so long ago compared to many people, knowing that your experience as a disabled immigrant in the 1970s was unique. This memoir on Amazon that I found called Twin Voices: A Memoir of Polio, the Forgotten Killer is so gross to me just from looking at it briefly. Maybe I’m too judgmental. The author seems to have no or little awareness or sense of themselves as having a disability identity. The main point seems to be about eradicating polio today, but not because we should generally be fighting for people’s health, but because the author’s life with polio is self-described as horrible. Yech. I have a lot of the same aversion to the medical model that you have, mom, and a lot of similar anger about its purported objectivity.

Sometimes when I run on like this I can kind of catch the ways I am replicating disconnection and dismissiveness more than being truly protective of my mother or myself or others, that I’m not really open or curious with safety rails on, that I’m just closed and tired and tight. Sometimes in these moments, I pontificate on the need for curiosity and questions, and then I try to get my mother to lead the way, to show me how to be brave the way I’m telling her we both should be. She’s my mother, after all, and I have relied on her to teach me my whole wide life.

What were your first questions about disability identity?

~ Karen ~

One of my earliest aware moments of being a child with a disability may have been when I was in Kysthospitalet (coastal hospital) and it started to occur to me that there were two groups of patients there. One group would go home and no one would be able to see that they might have been in the hospital. The other group which I belonged to would go home and people would see that there was something wrong with me, something wrong with my right leg. I was ashamed of being part of that second group. I had for years been going to sleep at night praying to God that I would wake up the next morning with two strong legs. I believed that God could perform miracles and if my faith in God was strong enough my polio leg would be gone, and I would have two normal legs.

Eventually I realized that my polio leg would not be transformed into a normal leg by some divine miracle. However, I still had faith that my repeated operations by Dr. Støren at Kysthospitalet would continue to improve my ability to walk and to make my polio leg look more normal. So although it would interfere with my last year at the Gymnas (secondary school), I did not resist when I was told that Dr. Støren wanted me to have another operation in the summer of 1960. That turned out to be a big mistake. I had been walking without a brace for ten years, but after that sixth and last operation my polio knee started buckling backwards so much that I ended up having to choose between wearing a long leg brace or fusing my right knee in a straight position. I chose to wear the brace because never being able to bend that knee seemed awkward and difficult to negotiate. The brace made me stronger and more able to walk, something I later came to appreciate a lot. But at first it was a serious blow to my vanity. I bought large, thick, pale stockings and wore them outside my brace, hoping to camouflage it, to make it less noticeable.

After becoming a special education teacher, I was able to accept my brace and I even wore mini skirts that exposed all the steel and leather and buckles and straps. No plastic or velcro was used to create individualized braces at that time. However, I still was ashamed of how I walked, how I moved. I still thought that the built environment containing lots of stairs and cobblestones was a challenge that was my responsibility to overcome. It was not until I came in contact with the Independent Living Movement and the Disability Rights Movement in the United States that some new ideas and thoughts helped me start consciously feeling differently about being a person with a disability.

When I first came to Access Living, I thought that my wheelchair was too big for our toilet at home. Now I know that our toilet at home is too small for my wheelchair.

I thoroughly enjoyed this conversion and the idea that a disability is not shameful, not something to be pitied. However, I could never completely shed the feelings that my polio had indeed held me back, had contributed to my low self-esteem and my social insecurities. My polio survivor friends told stories about how their parents had always told them that they were just as good and important as nondisabled kids. In contrast, the message I got from my parents was that there was something not just different about me, there was something wrong that they were determined to hide or fix. There were times that my parents, ashamed of my polio, tried to keep me from being seen.

My mother told me that when I was still a young child they took me to a faith healer who poured oil on my head and prayed to God to take away the effects of polio. I do not remember that event myself, but I have never forgotten the message that there was something wrong with me that my parents were begging their God to fix. When that did not work, my parents put their faith in the medical profession, and never questioned the advice they got from the doctors who wanted to operate on me and test their theories of what the results would be. At the age of eighteen, I had still not developed a sense of being in charge of my own destiny, I was stuck under the ice in the creek.

After becoming an elementary school teacher, I started teaching a first grade class in Grimstad, Norway. The system was set up to expect me to be the teacher for the same group of children from first to sixth grade. I did not follow that path, because the local school psychologist, Einar Guttormsen, suggested to the school district that I start a resource room for children with disabilities.

What do you want to ask about disability identity and disability studies today?

~ Karen ~

I think that my struggles with self worth was what you would call “deeply internalized disablism.” I read this article by Catapult Smith called “The Ugly Beautiful and Other Failings of Disability Representation” from October, 2019. Discussions and writings about disability identity are flourishing on the internet. There is more than I can begin to read. Another example is a research article by several authors that is titled, “Critical Perspectives on Disability Identity.” The authors examine the social construction of language, labels, and knowledge associated with disabilities, arguing in favor of critical and intersectional perspectives on disability identity. Edlyn Peña is writing about autism. Lissa Stapleton is a deaf African American woman. The Catapult website is describing some of the experiences I have had in my life, but it does not mention the possible impact of religious fundamentalism. I totally agree that we need to adopt an intersectional perspective on disability identity, and so would all my polio survivor friends, to the best of my knowledge. But none of us have been able to understand or explain how our privileged status as white, well educated, and relatively prosperous individuals has constrained our ability to be intersectional and broadly inclusive. The independent living movement has not been as effective as the psychiatric survivor movement has at reaching poor, homeless disabled individuals with a criminal history. The contrast between Paraquad and the Empowerment Center in St. Louis is telling and typical.

What has stayed the same in your thinking about disability? What has changed?

~ Karen ~

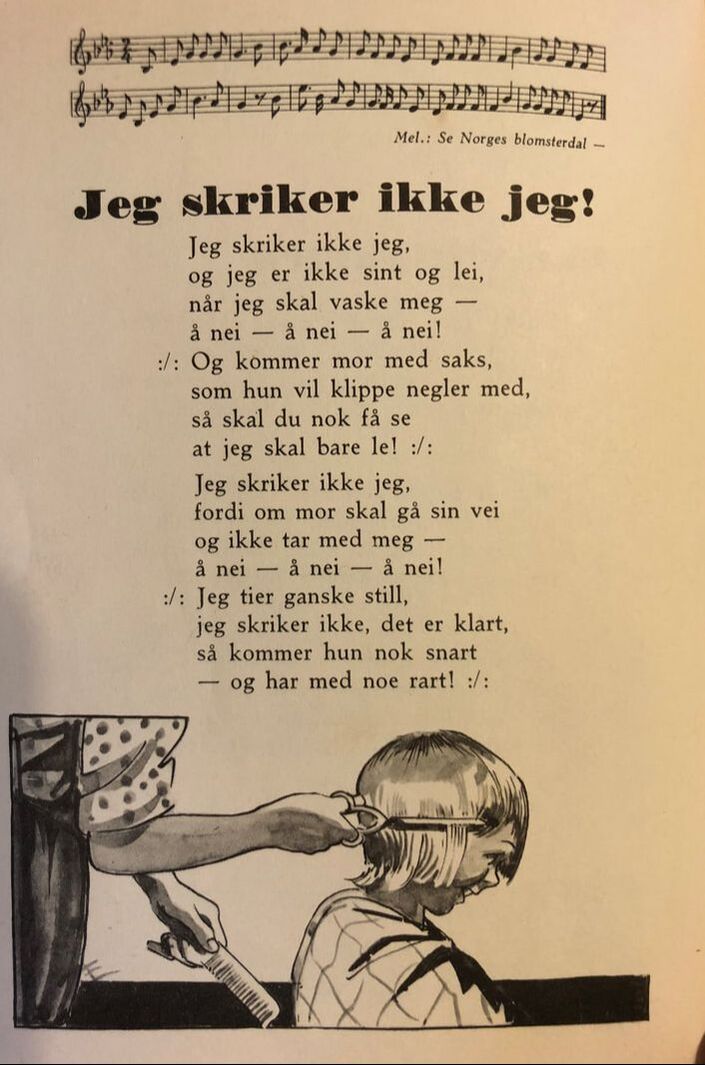

My thinking about disability has gone through some serious variations over time. As a child I thought that there was something terribly wrong with my right leg and I felt ashamed of it. I was ashamed of the way I walked, the way I moved around in the world. The shame was focused on the way I looked, I did not have many conscious regrets about not being able to run or dance, or be athletic in any way. But I was sad and depressed every time I was not included in activities like school field trips or 17mai (May 17) parades. I think my parents were ashamed of the way I looked as well. While they took for granted that my sisters would participate, they did not try to get me included in these activities. As a teacher, my mother would often take part in school related events, but making arrangements for me to be involved was not even discussed.

When I became a young teacher in Norway, I started participating in as many school activities as I could manage which meant just about all of them. The shame I felt was replaced by a strong desire to “overcome” my disability. I still saw my disability as my problem, my weakness, my challenge, but I did not want to let it stop me from living a full and responsible life. Accessible schools and other buildings were generally non-existent in the 1960s. And since I had not been around many disabled people yet, I thought it was too much to ask for, too few people would need the built environment to change that dramatically. As a graduate student in Chapel Hill, NC, in the 1970s, I met Ron Mace, a fellow polio survivor. His work as an architect has been very important.

When I first met Ron, I was still thinking that a disability was a challenge for an individual person to handle, not something that the world at large had anything to do with. It was not until I met Deborah Cunningham at the Memphis Center for Independent Living in 1983 that I began to see things differently.

While changing my thinking about these basic aspects of disability experiences, I have also kept some key perspectives remaining the same all along. Some people say that everyone is disabled in some way. Those who maintain that are most often people who I do not consider to be disabled themselves. They suggest that if a person is not able to perform in ways they would have liked to, that is a kind of disability. So for example if you are not good at dancing, or skiing, or swimming, or knitting, you are on the disability continuum, albeit not far out there. I totally reject that thinking. A disability is a difference that puts you in a different category from the norm. It may be visible or not. You may be able to pass in most situations or not. But it represents a reality in your life that society in general considers deviant. And most people with disabilities, whether they have grown up most or all their lives with that disability, or they have suddenly become members of our group because of an accident or illness know their status as a disabled person. Maintaining that everyone is disabled in some way, erases the reality of some hard life experiences shared by a large group of people.

I have a hard time distinguishing between my thinking and my feelings when trying to answer these question. My understanding and ability to express my opinions in clear language has changed dramatically over many years, but my memories of what I thought and knew at different times are foggy at best. Luckily I do have some written documents that I can draw on. One complicating factor is that I switched from one language to another, from Norwegian to English, during a time when my thinking and understanding was seriously shifting.

go FORWARD to Marginalia (part 6/12)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed